Chef de cave

The following text is from an article by Sophie Thorpe, 'Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: Champagne beyond the bubbles', that appeared in Fine+Rare

The man who crafts Cristal, Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, is one of Champagne’s most pioneering winemakers and a legend of the industry. When he took the helm at Louis Roederer in 1999, he became Champagne’s youngest Chef de Cave, aged just 33. In a rare move for the time, he fought to ensure he was in charge of both the vineyards and winery – knowing that the former would define the wines he produced. Since then he’s continued to push boundaries in the name of quality.

The house is one of the last to remain family-owned and – even more rarely for a Grande Marque – it owns an impressive 242 hectares of vines, providing enough fruit for around 70% of its production. Lécaillon transformed the way Roederer farmed, pushing first for an organic, then biodynamic approach – with half the vineyards now certified organic and half worked biodynamically, and no herbicides used at all. The results speak for themselves – with the house’s prestige cuvée Cristal arguably the finest and most sought-after in the region.

And the man himself is as effervescent as the wines he crafts. Lécaillon is clearly still enchanted by the world of wine –absorbed by its complexities and totally excited by it. Talking to him at a recent tasting, he explains his aim simply: "We are going beyond the bubbles."

For him, Champagne has traded on its fizz for too long. The wines were once sweet and served with dessert, they then became dry and were used as an aperitif, before becoming inextricably tied to celebrations – a curse that has limited the way Champagne is seen, and savoured. The industry has capitalised on its occasionality, but behind those bubbles – Lécaillon insists – is "a real terroir, a real wine".

It is this exact sentiment that is behind the Grower movement – something that Lécaillon clearly identifies with – however the movement also poses a threat to those trying to source fruit. For the little fruit Roederer doesn’t grow themselves (30% of their production), Lécaillon picks specific plots from around the region and tries to encourage growers to use a sustainable approach. The team will visit the vineyards in spring and summer, and choose the picking date with the grower. While today it’s sometimes tricky to persuade growers to change the way they farm, Lécaillon anticipates a generational shift will take place as more sustainability-invested children take over from their parents. Roederer used to buy fruit from Anselme Selosse, but – naturally – the star vigneron now keeps it all for himself. The fear is that the new generation won’t want to sell their fruit – leaving the Grandes Marques only lesser sites, farmed without the same stringency.

Everything Lécaillon has done at Roederer has been about championing site. He arrived at the house in 1989, but set off instantly for the property’s projects in Anderson Valley, California and then Jansz in Tasmania, returning to Champagne in 1994. Between 1996 and 1998, he worked on a soil study of the house’s vineyards, as well as an archive study – tasting wines back to 1876. When he took over in 1999, he separated all the plots – with 45 specific mid-slope chalky sites dedicated exclusively to Cristal, fruit for the Blanc de Blancs coming from their La Côte estate in Avize and the vintage wine based around Pinot Noir from their La Montagne estate in Verzy.

Changing the viticulture was the next step. In the 1970s, ’80s and even ’90s, Champagne’s soils were a literal dumping ground – with Paris’s rubbish used as "fertiliser". Lécaillon is one of many that has pushed for change in this area. He feels that organic farming produces better fruit with more dry extract and concentration, but also healthier vines that are stronger and more resistant to the vagaries of vintage – and climate change. Half the property’s vines are now farmed biodynamically – including all the plots used for Cristal.

In a bid to further champion their terroir, Lécaillon established the region’s first private nursery in 2015. He wanted to gather different massale selections from the Roederer vineyards – cuttings from pre-clonal vines that he feels have adapted to climate change and will be key to the house’s (and Cristal’s) future. He claims that it’s the biggest private collection of Pinot Noir in France, and they’ve now expanded the nursery to include not just Chardonnay and Meunier, but all seven of the region’s permitted varieties – including the little-planted Arbane, Petit Meslier, Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc. The Chef de Cave feels that field blends with these varieties could be the future with climate change – adding freshness to the wine. Over the last two decades, Lécaillon’s work in the vineyard has brought further freshness and precision to the wines – and the introduction of Collection was the latest step in that direction, a move to "bring [the wine] closer to the terroir".

A horse plowing the vineyards at Louis Roederer

Cristal might be the jewel in the house’s crown, but a non-vintage blend is any house’s calling card – representing the most significant volume produced (75% at Roederer) and the wine that reaches the most people. It is, Lécaillon says, always the hardest to produce, the most complex to blend – and yet also the one that receives the least attention.

Roederer’s Brut Premier was introduced in 1986, but back then Champagne was more marginal, viticulture and winemaking less advanced, and the battle was for ripeness. In vintage years, the fruit was actually ripe; the art of non-vintage blends was correcting the under-ripeness of the other years with reserve wines. Now, with climate change and the evolution of farming, Champagne has riper fruit than ever before, and an increasing number of vintage-quality years. "The battle now is not for ripeness, but for freshness," Lécaillon explains.

Collection 242 was released in September 2021, with many initially mourning the loss of Brut Premier; people, however, have been won round. As has become fashionable (along with the likes of Krug or even Nyetimber), the wine is "multi-vintage" or "MV" rather than "NV" or "non-vintage". In Lécaillon’s view, "NV" is "corrective", whereas, "MV is the story of the new Champagne". Their aim is no longer consistency, but to make the best possible wine in that year.

He points to 2002 as a pivotal year in the journey to Collection. It was a stunning growing season, with every plot producing wine of vintage quality – but to build a consistent non-vintage wine, they had to "destroy" the quality of each. While Lécaillon feels Brut Premier was an "outlier" in the range, Collection is "more Roederer", "more Champagne" – which, for him, has to have an oyster-shell salinity.

A key part of developing Collection was creating a perpetual reserve. Held in an enormous 10,000hl stainless steel tank, this reserve is a constantly evolving blend of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Started in 2012, it contains wine from every harvest since, stored without oxygen, in the depths of their cellar where the temperature is cool and stable. This, Lécaillon feels, brings extra texture, depth and a "vintage dimension" to Collection – without the heaviness that he saw in Brut Premier.

The blend also includes more traditional reserves aged in oak (around 10% of the final blend), all with fruit from the younger vines in plots otherwise dedicated to Cristal (only 20-year-old vines make it into the prestige cuvée). The most important element here is that the toasting of the barrels is very light, what Lécaillon describes as a "white toast", so that it doesn’t dominate the terroir.

Collection 242 was followed by 243 last year – and they are two extremely different wines, the 243 riper and richer versus 242’s more mineral expression. This – for Lécaillon – is what makes an "MV" approach so much more interesting, for both him and wine-drinkers. It is, he tells me, "a blank page every year".

With everything from zero-dosage experiments to rootstock trials, Lécaillon is constantly looking for ways to improve – with a relentless zest and enthusiasm. For this vigneron, a blank page isn’t daunting – it’s a chance to express his terroir.

About the winery

Louis Roederer is one of the last Grande Marque Houses in Champagne that is independent and family owned, with 7th generation Frederic Rouzaud currently at the helm. "It’s a family business, family managed. There are just 10 family members – this is very important and gives us a lot of control," says Chef de Cave Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon.

From the 100 hectares acquired in 1850 by Louis Roederer, the Domaine today extends over 240 hectares, providing enough fruit for around 70% of its production. All the Roederer vintage wines are 100% estate grown. "We are a grower," says Lecaillon. "When you taste Vintage Roederer – Cristal, Cristal Rosé, Blanc de Blancs, Vintage, or Vintage Rosé – we are a grower."

It's only for the Collection (formally Brut Premier) that the House buys in grapes, where 40% of the fruit is sourced from long-term contracted growers. "We buy mainly Meunier, because our vineyards are mainly located in Grand Cru or Premier Cru, and as you know these are mostly Pinot Noir and Chardonnay," says Lecaillon. "I only have 6 hectares of Meunier. This doesn’t mean we don’t like Meunier: it just means that we have soils that are chalky. Chalk is not a Meunier soil."

Since 1999, under Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, Louis Roederer has championed organic and biodynamic practices. In 2012 Louis Roederer became the largest biodynamic producer in Champagne. Today, half of Louis Roederer's vineyards are certified organic and half worked biodynamically, as part of what Lécaillon says is a work in progress. No herbicides are used at all.

History

In 1833 Louis Roederer inherited the Champagne house Dubois Père et Fils from his uncle, Nicolas-Henri Schreider, for whom he had been working since 1827. Roederer changed its name and began purchasing Grand Cru vineyards in Vallée de la Marne. This approach contrasted sharply with other Champagne Houses, who at the time, purchased all of their grapes. Louis Roederer nurtured his vineyards, familiarized himself with the specific characteristics of each parcel and methodically acquired the finest land.

Louis turned out to be a shrewd businessman, who managed to develop champagne exports and who convinced many members of the elite to try out his wines. His most notable encounter happened in 1867, three years before his death, when he showcased his champagne at the Universal Exhibition in Paris. There, he met the Czar Alexander II of Russia, who fell head over heels for Roederer's champagne cuvées and promised to order wine from the French entrepreneur regularly.

Louis' business acumen, astute vision of the future, together with his belief that all great wine depends on the quality of the vineyard, helped to establish the fame and reputation of the House of Louis Roederer. He died in 1870.

After his death, his son Louis Roederer II took over the running of the house and began to export his Champagnes to the United States and Russia. Czar Alexander II of Russia wanted his champagne to be delivered in clear bottles with flat bottoms, as he had many enemies who were adept at using explosive devices and poison. In 1876, Louis fashioned the famous 'Cristal' cuvée for the Tsar and became the sole supplier to the Russian Court. The relationship between House Roederer and the Russian nobility would be a lasting one and the Czar's coat of arms still appears on the champagne's labels.

Louis Roederer II died suddenly in 1880 and the winery was managed firstly by his sister Léonie, followed by her son Léon Olry-Roederer who took over the reins in 1880 until he died in 1932.

For the next 42 years, from 1933 until 1975, the winery was managed by Léon's young and strong-minded widow, Camille. She ran the Champagne House with formidable intelligence and singular dynamism, and against all odds, held on to the near-bankrupt House and then succeeded in bringing back the glory days. She nursed the House back to a profitable enterprise through the Great Depression and World War II, and continued the tradition of buying great vineyards when prices had dropped after the war.

Camille Olry-Roederer loved horse racing and owned one of the most famous stables in the world. She also embraced the more festive and pleasurable aspects of champagne, holding many lavish receptions in the family’s Hôtel Particulier in Reims. These parties had a lasting impact on the history of the House and introduced a whole new generation of wine lovers to the joys of Louis Roederer Champagne, including Gustav V and VI of Sweden, Frederick IX of Denmark and Queen Elizabeth II.

Upon Camille's death, her grandson Jean-Claude Rouzaud ran the house until 2006. With a background in oenology and agronomy, he brought more cohesiveness to the prestige champagne brand. The House diversified its business interests under his management, purchasing shares in the champagne house Deutz and the legendary Château Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande, in Pauillac.

Jean-Baptiste Lecaillon joined Roederer in 1989. After several stints at Roederer's subsidiaries abroad he returned to Reims in 1994 to work as chief enologist. In 1999 he became Chef de Cave and has been a leading force in Roederer's biodynamic approach.

The Louis Roederer House has remained an independent, family-owned company and is now managed by Jean-Claude’s son, Frédéric Rouzaud, who represents the seventh generation of the lineage. Today Louis Roederer’s annual exports total three million bottles and the brand’s prestigious cuvées have an enviable following among wine drinkers, critics, and investors worldwide.

Vineyards

Louis Roederer has always invested in their vineyards. The original Louis Roederer began purchasing Grand Cru vineyards in Vallée de la Marne and familiarized himself with his different vineyard parcels. Subsequent generations have retained a firm focus on the vineyards.

Today the House owns over 242 hectares (594 acres), predominantly from Grand Cru and Premier Cru villages. The estate vineyards account for 70 percent of production and all the Roederer vintage wines are 100% estate grown.

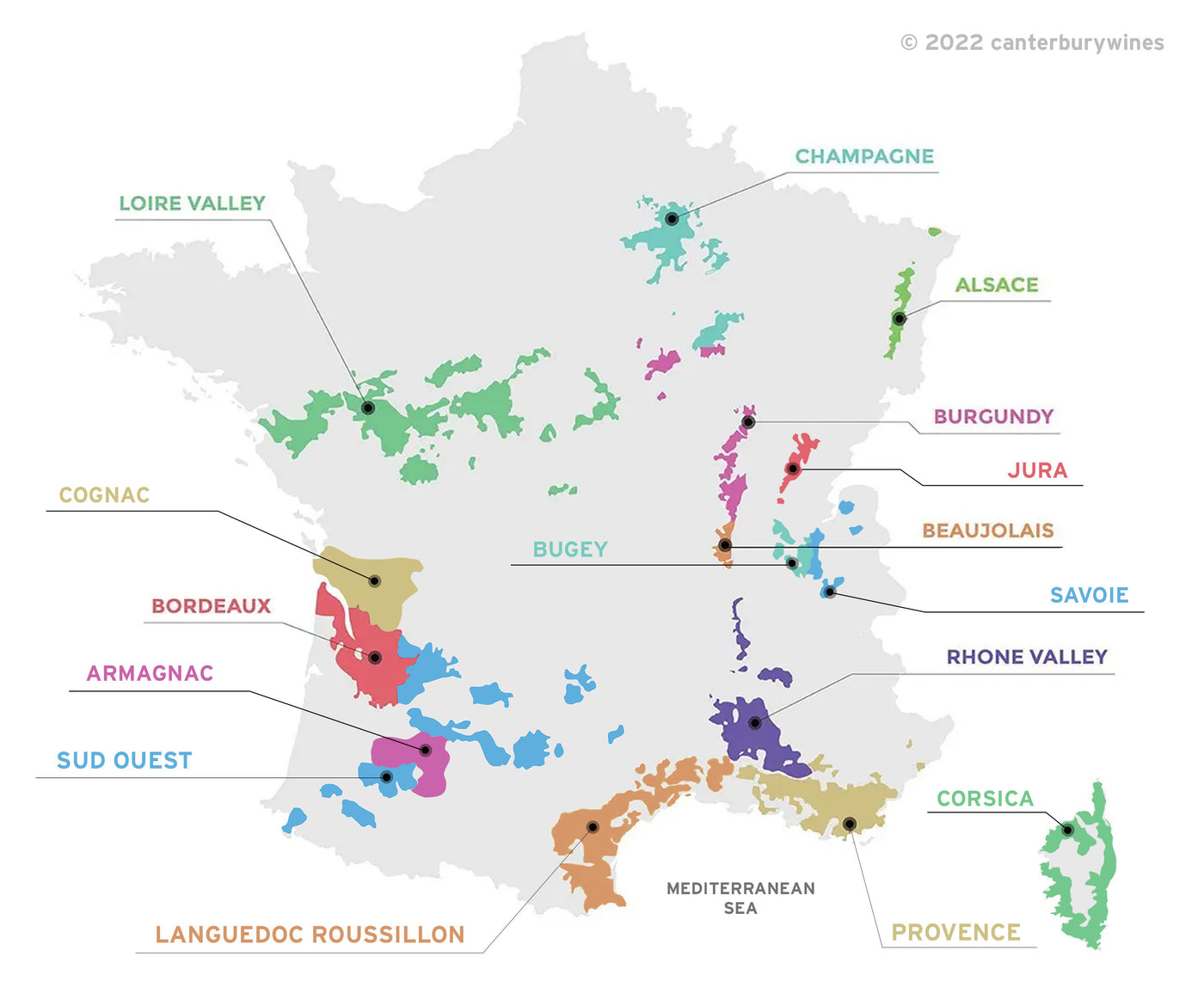

Roederer owns vineyards in the Côtes des Blancs, Vallée de la Marne and Montagne de Reims regions. The House owns more than 80 hectares in the Côtes des Blancs, with a vineyard team based in Avize. They also have a team in the Vallée de la Marne, in Aÿ, where they have 65 hectares, and another team in the Montagne de Reims looking after some 70 acres.

Roederer, under Chef de Cave Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, has split up the vineyard holdings so that specific plots are designated for particular cuvées. The aim is to have the same people tending the same vines year after year. The grapes in each plot are meticulously gathered by hand, collected in the buckets and pressed on the site of the harvest. The pressing process is a delicate one because the berry must not alter the colour of the juice, which must maintain its golden hue and clarity. The plot-by-plot vinification ensures that the origins and traceability of the grapes are preserved and provides a record of the fruit from each plot.

Inside the cuves and the tuns, the wine from each plot develops into an 'entity' in its own right, with its own qualities - and sometimes weaknesses - that the oenologists fully nurture and exploit. The specific characteristics of each cru are preserved until the blending process.

Private nursery vineyard

In the village of Bouleuse, near Reims, Roederer has a very important vineyard - with 11 out of the village’s 13 hectares, they effectively own the village. They selected the vineyard in 2013 to plant American rootstocks on which massale selections from their own vineyards are grafted. This means they can plant young vines that have wholly been grown in their own sites, without using an external vineyard nursery. They have been granted the status of 'pepiniériste privé' which allows them to do this. They also grow young vines without American rootstocks, using grapevines from before the Phylloxera crisis, to see if there is a difference in taste.

"It’s very important because it is a bit away from the mainstream of vineyards and we have all our nursery there: we do all massale selection and grow all our own rootstocks," says Lecaillon. "We have the unique position in Champagne of having our own private nursery. We are the only house with this position. We believe the challenge of the 21st century will be genetic. This is why we really focus on massale selection and we believe there is a huge biodiversity that we can explore. This could answer a lot of questions of the 21st century, such as climate change. We have some Pinot Noir clones that can ripen three weeks apart. From one Pinot Noir to another you reach the same alcohol level with three weeks difference. This is huge. In the context of global warming you can imagine planting late-ripening Pinots as opposed to the early-ripening Pinots planted in the 1960s and 70s."

Biodynamic farming

Roederer has always farmed as sustainably as possible and, in 2002, was the first Grande Marque house to adopt biodynamic farming. Today, half of Louis Roederer's vineyards are certified organic and half worked biodynamically. They are the largest biodynamic producer in Champagne.

"Out of the 242 hectares, we have 122 hectares – a bit more than half – organically certified," says Lécaillon. "We are increasing our certification every year. We have 10 hectares that are Demeter biodynamic certified as well, but we do biodynamics on all the estate. All the organic vineyards, except three plots that we keep as a control, are biodynamically farmed. We do all our biodynamic composts, we do the preps on all the organic estate."

"We started our conversion to biodynamic farming in 2000. We switched the estate slowly. In 2007 all Cristal Rosé was biodynamically farmed. Since 2012, Cristal is completely farmed biodynamically, and since 2006 we have Brut Nature that is 100% biodynamically farmed."

They can't be biodynamically certified on more of the vineyard area because they buy in fruit for the Collection (previously Brut Premier). "I can be organic, but I cannot be Demeter because I am fermenting some wines here that are not Demeter certified. If you want to be Demeter certified you have to be 100%, and for Brut Premier I am buying fruit," he explains.

The Wines

Collection Cuvée

The House's calling card, Roederer’s Brut Premier, was introduced in 1986. It was a traditional three-way blend of around 40% Pinot Noir, 40% Chardonnay and 20% Pinot Meunier, with the addition of a minimum of 20 percent reserve wines.

The 'non-vintage' Brut Premier was replaced by the 'multi-vintage' Collection 242 in September 2021 when Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon's aim was no longer consistency, but to make the best possible wine in that year.

The Collection cuvée each year is a bespoke vinification, made up largely from the current harvest, a significant percentage from the Perpetual Reserve* and around 10% of reserve wines that are aged in French oak foudres. For example, Collection 244 is made up of 54% of the 2019 harvest, 36% of the Perpetual Reserve and 10% of oak-aged reserve wines.

* A key part of developing Collection was creating a Perpetual Reserve. Held in an enormous 10,000hl stainless steel tank, this reserve is a constantly evolving blend of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Started in 2012, it contains wine from every harvest since, stored without oxygen, in the depths of the House's cellar.

The Champagne House wanted to reflect the historical origins of the Brut Premier in the Collection blend. To this end, 1/3 of the blend is from their 'La Rivière' Estate, 1/3 from their 'La Montagne' Estate and 1/3 from their 'La Côte' Estate.

Vintage Brut

The Vintage, a blend of around 70% Pinot Noir and 30% Chardonnay, is a testament to an exceptional year. It aims to capture the unique expression of the Pinot noir from the 'La Montagne' estate, which comes mainly from the original vines purchased by the Champagne House in the village of Verzy. Around one-third of the wine is oak-aged. The Vintage cuvée is generally matured on lees for 4 years and left for a minimum of 6 months after dégorgement (disgorging) to attain perfect maturity.

Vintage Rosé

The Vintage Rosé, a blend of around 60% Pinot Noir and 40% Chardonnay, is a snapshot of a year. The Rosé comes from 35 small staggered plots on the warm terroirs of the 'La Rivière' estate, from the vines in the Cumières and Chouilly Crus. Like the Brut Vintage, the Rosé is generally matured on lees for 4 years and left for a minimum of 6 months after dégorgement before release.

Vintage Blanc de Blancs

The 100% Chardonnay Vintage Blanc de Blancs is inspired by the Champagne House’s savoir-faire in the harvest of a single year. The fruit is sourced from hillside plots in the Grand Cru village of Avize in the heart of the 'La Côte' estate. This champagne draws its strength from the intense chalkiness of these limestone soils which lend it its infinite freshness. With time, this champagne reveals the power and identity of this great terroir. The Blanc de Blancs Vintage cuvée is generally matured on lees for five years and left for a minimum of 6 months after dégorgement before release. 10-20% of the wine is vinified oak casks.

Cristal

Cristal was created in 1876 and was the first Cuvée de Prestige launched in Champagne. It is a blend of 60% Pinot Noir and 40% Chardonnay from seven Grand Cru villages in the region. Around 1/3 of the wine is sourced from their 'La Rivière' Estate, 1/3 from their 'La Montagne' Estate and 1/3 from their 'La Côte' Estate (in the sub-regions of Vallée de la Marne, Montagne de Reims and Côtes des Blancs respectively). The Pinot Noir comes from the Grand Cru villages of Aÿ, Verzy, Verzenay and Beaumont-sur-Vesle, the Chardonnay from the Grand Cru villages of Mesnil sur Oger, Avize and Cramant.

Around a third of the wines are vinified in oak, the remainder in steel. Malolactic fermentation is blocked. The wine spends 6 years on lees in Louis Roederer’s cellars and after dégorgement is left for a further 8 months before it is released.

Cristal Rosé

In 1974, almost 100 years after the launch of Cristal, Jean-Claude Rouzaud created the Cristal Rosé cuvée. He selected old-vine Pinot noir grapes from the finest Grand Cru vineyards at Aÿ, which are now cultivated according to biodynamic principles. The unique calcareous clay soil, which gives the grapes an exquisite minerality, enables the vines (in the best years) to attain exceptional fruit maturity, complemented by a crystalline acidity.

Cristal Rosé is a blend of 55% Pinot Noir and 45% Chardonnay from three Grand Cru villages in the region. Around 1/2 of the wine is sourced from their 'La Rivière' Estate and 1/2 from their 'La Côte' Estate (in the sub-regions of Vallée de la Marne and Côtes des Blancs respectively). The Pinot Noir comes from the Grand Cru village of Aÿ, the Chardonnay from the Grand Cru villages of Mesnil sur Oger and Avize.

Comprising around 20% of wine matured in oak tuns, Cristal Rosé is produced using the saignée (bleeding) process after cold maceration. The cuvée is aged, on average, for 6 years in Louis Roederer’s cellars.

Brut Nature

In October 2014, Frédéric Rouzaud added the latest vintage cuvée to the portfolio, the 2006 Brut Nature. Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon says of the Brut Nature, "This is, without a doubt, the least 'Roederer' in style of all our Champagnes, as well as the most modern.' The collaborating designer Philip Starck wanted to create a modern Champagne – a wine of the future.

This inspired Lécaillon and his team to go against all classic rules of Champagne making. The wine is made from a single year, one terroir, picked in one day, co-pressed and co-fermented, with less mousse (a lower pressure of 4 atmospheres of pressure when typically most champagnes are at 6 atmospheres) and no dosage. The essence of this cuvée is its uniqueness.

The cuvée is a blend of Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Pinot Meunier - the percentages of each varietal vary markedly from year to year. The grapes are sourced from three plots in the Cumières Cru in their 'La Rivière' Estate. The Cumières clay hillside on the banks of the Marne river, turned towards the sun and basking in its light, is a hallowed enclave. These black soils have long been known to produce generous, opulent and intensely fragrant grapes, and in warmer years (when the Brut Nature is made) the grapes obtain incredible ripeness and a higher vibration which gives a lovely contrast between fruity intensity and salinity.

Even if Lécaillon feels they can make a similar wine in sun-drenched years, he stresses that "the next vintage will be different, as the aim of the cuvée is to express the essence of this specific place in a specific year."