"Moët Imperial is a little bit of everything. That’s the beauty of that wine. There are so many elements involved. Maybe where a Vintage is for a certain special moment, for me Imperial is for every moment. What I like about Imperial is the idea of spontaneity. Not being obliged to wait for a special occasion. Not being obliged to have the right temperature and the right glass, but just 'Let’s have a glass now.' And you know that if you have a glass of Imperial, you’ll be very happy with your glass. It’s the kind of champagne that always seduces and delights, whatever the circumstances.

Each year, we face the awesome challenge of re-creating the Moët & Chandon Impérial with the same recognisable taste that is beloved around the world, despite having to use grapes that, at each harvest, are never the same in aroma or ripeness. To achieve both consistency and quality, we accompany the process of winemaking at every stage, from the blending of still wines made from three grape varieties within months of the harvest, through the careful elaboration and the bottling of the same Champagne style at Moët & Chandon year after year." Benoît Gouez, Chef de Cave

Brut Impérial was first released in 1869 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Napoleon Bonaparte, diminutive lover of bubbly and close personal friend of Jean-Rémy Moët, the gregarious vintner and grandson of house founder Claude Moët.

In its day, Impérial was something of a revolution. Less than one percent of champagne produced was labelled 'brut' (and even the brut of 1869 was much sweeter than today’s dry version). But the relative lightness of Brut Impérial - its elegance above all - has endured. Moët Impérial today is nothing short of an icon, its gold foil–wrapped bottle a universal symbol of celebration. It is by far the biggest selling Champagne in the world - around 20 million bottles are produced each year, which is about 7% of Champagne’s total production.

Brut Impérial is a blend of over 200 crus, of which 20% to 30% are reserve wines specially selected to enhance its maturity, complexity and constancy. The assemblage reflects the diversity and complementarity of the three grape varietals used; the full body of Pinot Noir (30 to 40%), the suppleness of Pinot Meunier (30 to 40%) and the finesse of Chardonnay (20 to 30%). The wine is aged for a minimum of 2 years on lees and sits for 6 months after disgorgement before release.

Impérial has become fresher and less sweet over time. When Benoît Gouez arrived in 1998 the dosage was 13g/l. "We trialled it and found we preferred 11g/l," he says, "But we kept 13g/l for customers." The dosage was subsequently reduced to 9g/l and today sits at 7g/l.

The following text is taken from an article by Sam Kessler that appeared in The Oracle Time, April 2017.

Drinking champagne is easy, so much so that I find myself doing so without meaning to on all too many occasions. Making it on the other hand is far, far less so.

Most educated epicureans are well aware that each bottle of champagne is a blend of different wines from different vineyards around the geographical region. Many even know the three main grapes that entails: Pinot Noir, Meunier and Chardonnay. Very few however really appreciate what that means for the winemakers themselves.

In the case of the world’s largest champagne house, Moet & Chandon, head winemaker Benoît Gouez has an unenviable task. We were fortunate enough to have a private tasting with Benoît and… well… we won’t be starting a champagne house any time soon.

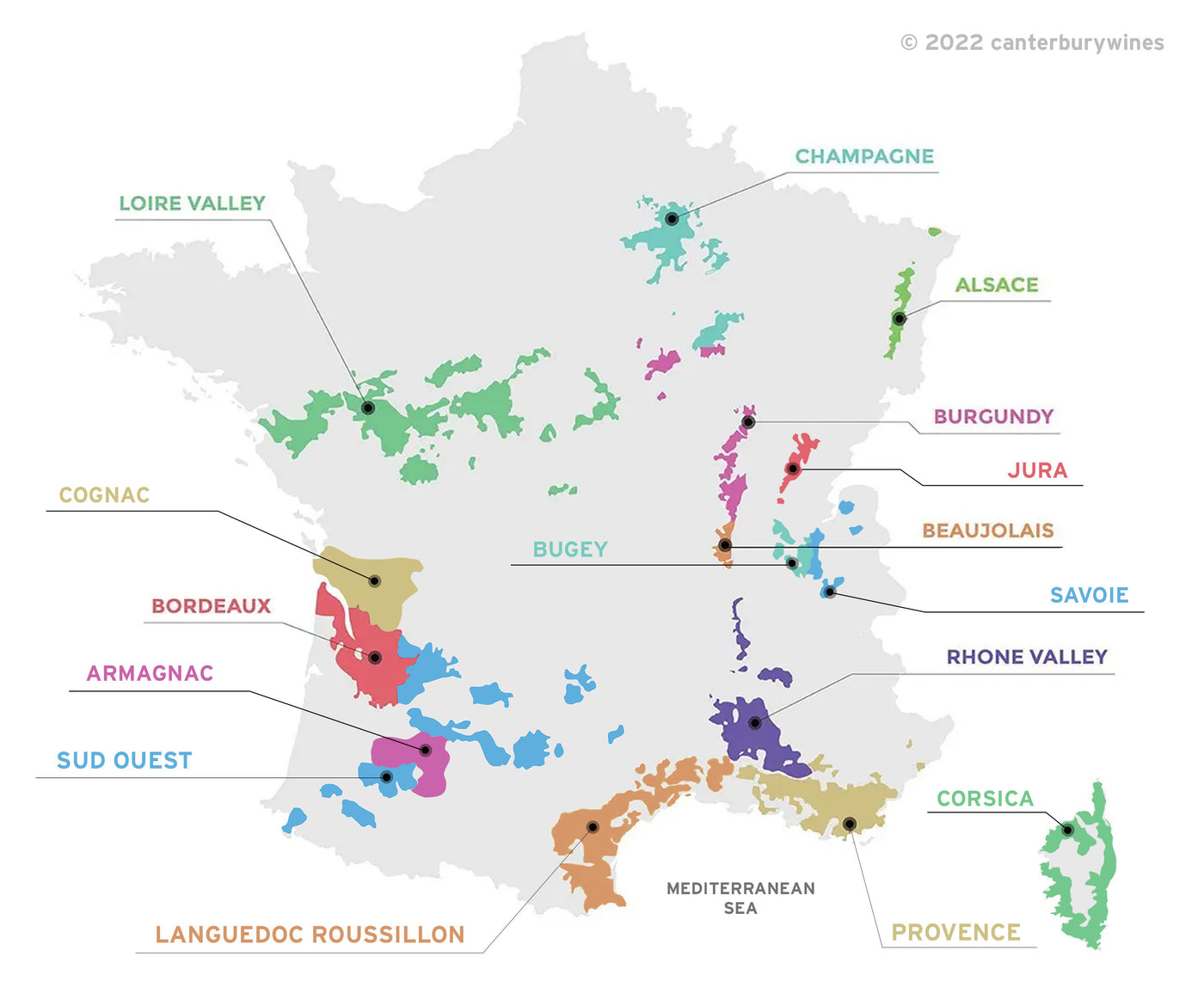

For of all are the sheer number of wines that get used at Moet & Chandon. Three different grape varieties yes, but the sheer number of vineyards these come from is staggering. Each vineyard has its own unique terroir, the landscape that gives the grapes their characteristics. This in turn means that, even if each uses the same grapes and same quality of grape, the wines coming from each will be completely different.

Even then, that’s never the case. Champagne has no uniform climate. It’s myriad different landscapes and terroir variances, not to mention weather that makes Britain seem consistent, all mean that every harvest is completely different.

For some wines this wouldn’t be a problem; indeed for some champagnes it’s not. Variance is what makes a vintage a vintage, a snapshot of the region on a given year. But imagine what that means for something like Moet Imperial.

Imperial is the signature of the house, the wine that defines its character to the world at large. In essence it’s the truest expression of what Moet & Chandon is. The key to that is consistency. Each It’s Benoît’s job to ensure that consistency in the face of all adversity. Fortunately for him, champagne has learned over the years that when one grape suffers, another flourishes. Where one year the Chardonnay gets destroyed by late frosts, the Pinot Noir is better than ever.year it must be the same, over and over without fail, regardless of the quality of grapes that year.

The trick that Benoît has mastered is how to balance the good with the bad. The same volume needs to be made after all, and the same elements have to go into it to create that consistent profile of Moet Imperial. Where one component wine is lacking in body, another needs to be positively overweight. Where on lacks acidity, another needs to be razor-sharp.

During the course of the harvest and following winemaking period Benoît will sample hundreds and thousands of wine, equating to about 30 a day. He and his team of tasters will work through everything, pinpointing where each is strongest in order to better understand how they can fit into the Imperial puzzle.

So far so tricky, right? What we’ve yet to factor in however is the reserves. Reserves are the good wines that Benoît keeps each year, holding them back for a particular blend or in case of emergency. These can be a lifeline when the grapes of a particular harvest are lacking, adding some much-needed oomph to the blend.

They are not however something Moet can afford to go overboard with. There’s no guarantee that a wine of that quality will be replenished the next year. If it’s earmarked for a certain blend and there’s not enough to go around, disaster strikes. Reserves may be an invaluable resource, but they add yet another layer of complexity to an already-labyrinthine proposition.

So what’s Benoît’s secret to keeping the consistency of Imperial? Quite simply there isn’t one. There’s no shortcut, no easy solution. Each year is fraught with next-to-impossible decisions, decisions that only experience can account for. Nobody knows Moet like Benoît, neither the profile of their wines nor the contents of their cellars. In short, there’s nobody alive that could do what he – and indeed the Chef de Cave of any champagne maison – can do.

So next time you buy a bottle of Imperial, next time someone questions the quality of a non-vintage over a vintage, just explain to them clearly and eloquently just how much work went into creating that beautifully balanced, invariably consistent bottle of wine. If you can’t… well, we’re probably in the same boat.