The story of grange

1931

In a sign of Max Schubert's determination to make his mark on Australia's wine industry, he did whatever he could to get his foot in the door at Penfolds, joining the company as a messenger boy in 1931. By 1948, at the age of 33, Max Schubert became Penfolds first Chief Winemaker.

1950

In the latter part of 1950, Schubert was sent to Europe to investigate winemaking practices in Spain & Portugal. On a side trip to Bordeaux, Schubert was inspired and impressed by the French cellared-style wines and dreamed of making 'something different and lasting' of his own.

1951

Back in Adelaide, in time for the 1951 vintage, Max Schubert set about looking for appropriate 'raw material' and Shiraz was his grape of choice. Combining traditional Australian techniques, inspiration from Europe and precision winemaking practices developed at Penfolds, Schubert made his first experimental wine in 1951.

1957

Max Schubert was asked to show his efforts in Sydney to top management, invited wine identities and personal friends of the board. To his horror the Grange experiment was universally disliked and Schubert was ordered to shut down the project. What might have been enough to bury Grange in another winemaker's hands, only made Max more determined to succeed.

Late 20th Century

Max continued to craft his Grange vintages in secret, hiding three vintages '57, '58 and '59, in depths of the cellars. Eventually the Penfolds board ordered production of Grange to restart, just in time for the 1960 vintage. From then on, international acknowledgment and awards were bestowed on Grange, including the 1990 vintage of Grange which was named Wine Spectator's Red Wine of the Year in 1995.

Today

Grange's reputation as one of the world's most celebrated wines continues to grow today. On its 50th birthday in 2001, Grange was listed as a South Australian heritage icon, while the 2008 Grange vintage achieved a perfect score of 100 points by two of the world's most influential wine magazines. With every new generation of Penfolds winemakers, Max Schubert's remarkable vision is nurtured and strengthened.

The following text is taken from an article by Ken Gargett in Quill & Pad, https://quillandpad.com

The following text is taken from an article by Ken Gargett in Quill & Pad, https://quillandpad.com

Grange is one of the best-known stories in Australian wine, always worth recapping, especially as a bottle of the very first vintage, 1951, sold at auction last month for AUD$157,624. Not bad for a wine that was never released commercially – it was simply considered an experiment at the time and is apparently only just this side of undrinkable these days.

Grange had an unlikely genesis. Penfolds' head winemaker back in the late 1940s was the legendary Max Schubert. In those days, the market was very much focused on fortifieds, with table wines a distant second. Schubert made several visits to Spain and Portugal to study fortified making, but he had a strong interest in table wines and on the way home he ducked up to Bordeaux for a few days.

Schubert was blown away by what he saw there and returned determined to create an Australian "First Growth." Of course, easier said than done.

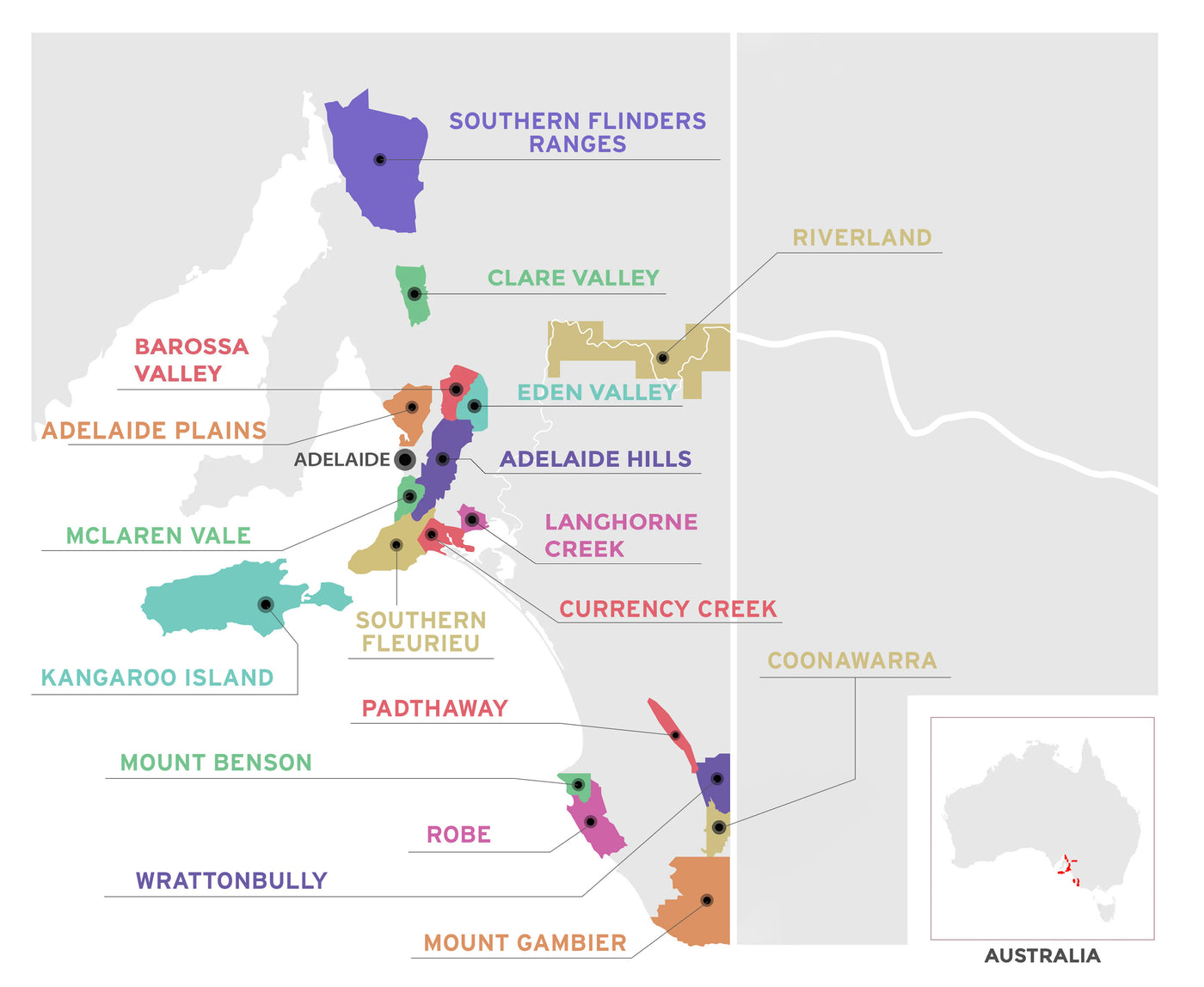

The first problem was funding it, though his employers were largely supportive of his experiments provided they did not get in the way of his real work – which in those days was very much on various fortifieds rather than table wines. First Growths tend to be heavily Cabernet Sauvignon dominant with varying amounts of other varieties, especially Merlot. Well, in the late 1940s, early 1950s in Australia, good luck finding much of either, especially Merlot, at the level of quality Schubert required. What we did have, in abundance, was Shiraz. At this stage, Shiraz was dominant even in regions that would become so famous for Cabernet such as Coonawarra.

In addition, First Growths spent time maturing in new French oak. At that stage, American was the oak most commonly found in Australia; there was simply not the quantity or quality of French oak available. So new American it was. While First Growths (indeed, all the top Bordeaux) were from single estates, Australia was all about blending, not only vineyards but regions.

So, the result would be a wine made mostly from Shiraz – only a few Granges over the years have been 100 percent Shiraz, most having a small percentage of Cabernet. It would be sourced from a wide range of regions and matured in new American oak. It has ever been thus.

So nothing at all like a First Growth then, but it started a line of wines that have long been generally considered as Australia’s finest. Personal preference might take one elsewhere and there are a number of exceptional contenders. But Grange has the runs on the board.

The first Grange, an experimental wine, was the 1951 and Penfolds has never missed a vintage since then. The first intended for commercial release was the 1952. Schubert’s intention was a wine that could match great Bordeaux in aging ability, so it was into the cellar with the first vintages for as long as he could get away with. After some years, he finally brought them out for a tasting for the Penfolds hierarchy (Penfolds headquarters was situated half a continent away in Sydney so the daily goings-on at Magill were of little interest). But as Schubert said, that hierarchy had become "increasingly aware of the large amount of money lying idle in their underground cellars at Magill."

To say the unveiling was a disaster of near Biblical proportions would be an understatement. The wines were hated, even ridiculed.

Schubert was devastated. He was inordinately proud of these wines, believing them to be exceptional. The tasting included vintages 1951 to 1956. The wines were treated with contempt. One well-known expert's assessment was, "Schubert, I congratulate you. A very good, dry port, which no one in their right mind will buy, let alone drink." Another compared them to "crushed ants."

Yet another thought he’d take advantage of the situation and offered to take a few dozen off Schubert's hands, but he expected them for free as he thought them not worth any money. One wanted some for use as an aphrodisiac, believing the wine to be like bull’s blood, hence something that would, "raise his blood count to twice the norm when the occasion demanded." A young doctor requested some as an anesthetic for his girlfriend (the mind boggles as to why this was required – and given his position as a doctor, why he did not have access to something more suitable).

It is worth noting that wines like 1952, 1953, and 1955 are now considered to be some of the greatest ever made in Australia. The 1951 is now little more than a curio and I doubt anyone is paying AUD$150,000 for the pleasure of drinking it. It is for collectors only.

After the debacle, the order came from Sydney: "Cease production."

Despite knowing full well that defiance of such instructions would end his career, Schubert was so convinced as to the ultimate quality of these wines that he ignored the directive. From 1957, he made the wines in secret. Of course, this meant that he could not add the usual quantities of new oak to the budget among other things – there is only so much you can hide from bean counters, even long distance. But the wines were made and hidden away in the depths of the cellars under false names and records. This gave us the "hidden Granges" of 1957, 1958, and 1959.

At the time Penfolds still had stocks of the early Granges and little idea what to do with them. Schubert entered them in shows – wine shows are very important to the Australian wine industry. Not surprisingly, they started to not only win medals but to dominate the shows. Naturally, this caught the eye of the hierarchy, and the decision was made to reverse the earlier edict. Schubert was instructed to recommence production. I can find no record of the reaction by the Penfolds board when it discovered that he’d never stopped, but I would love to have been the proverbial fly on the wall.

Peter Gago

The following text is taken from an article by Ken Gargett in Quill & Pad, https://quillandpad.com

Peter Gago has what many people in the wine world think is the best job on the planet. He is chief winemaker for Penfolds, based in South Australia and one of Australia’s oldest wine producers.

Max Schubert created Grange with the experimental first wine, the 1951, after he returned from Bordeaux and wanted to establish an Aussie First Growth. The story of Grange has been told many times, and as fascinating as it is I won’t rehash it again. Schubert ruled at Penfolds right through to the 1976 vintage, when he handed the reins to Don Ditter. Ditter made the wines right through to the 1986 vintage when John Duval stepped up. Duval was chief winemaker until the 2002 vintage, when he left to do his own thing, very successfully.

Since that time, Peter Gago has been the chief winemaker. It should be noted that although the role of chief winemaker at Penfolds will always be inextricably linked with Grange, there are a great many other wines in the portfolio for which this position assumes ultimate responsibility.

Alongside the winemaking, in which he is still heavily involved, a usual week in non-Covid times sees Gago flying around the world to tastings, dinners, events, festivals, and promotions. I suspect that only David Attenborough (outside of pilots and crew) has racked up more flying miles. I remember seeing him one day when he seemed even more pleased with the world than usual. Turns out he’d just run into his wife, Gail, now retired but a long-term and highly regarded member of the South Australian parliament, at the airport. Gago had not been aware that they would both be in the same country that week, let alone cross paths, such is his usual peripatetic lifestyle.

Gago has friends and admirers all around the globe, from the rich and famous to young, aspiring wine lovers, and will spend time talking to them all. I suspect that if he wanted to start dropping names, the din would reverberate for days, but you could not find a humbler man. Gago is a serious music buff and you’d be amazed at the number of rock stars who revere him, much in the way their fans might do for them (for instance, after crawling over broken glass to get a ticket to a Bruce Springsteen concert I saw Gago sitting in prime seats with Springsteen’s family, after which they went for dinner and knocked off a few bottles of Grange).

Gago is probably as close to a rock star himself in the world of wine, although perhaps more modest rather than flamboyant. And I have no idea if he can sing.

The thing that most amazes me with Gago is that every time you talk to him, he is bubbling with genuine enthusiasm, not just for Grange but for all his wines. He just loves what he is doing. One gets the feeling that every morning he wakes up and pinches himself to make sure it is real.

Among his many attributes, Gago has the gift of the gab like few others. Only once have I ever seen him lost for words and caught off guard. Many years ago, at the annual release – held in a very fancy location near the shores of Sydney Harbor; it is always a fancy location somewhere and also always includes great champagne to kick off the day as Gago is fanatical about the world’s best bubbles – the then current chairman or CEO of whichever corporate entity was then the owner of Penfolds attended the day. Forgive me for my failure to remember just where the corporate snakes and ladders left Penfolds that day and for failing to remember the relevant gentleman’s name. He had only been appointed as a temporary executive while the search for a more permanent one was ongoing, but unlike any of the CEOs before and after, this man had a genuine interest and came to a couple of tastings to learn.

Anyway, as we sipped our champagne on the lawns overlooking Sydney Harbor and chatted, our friend suddenly posed a question to Gago. He had been meaning to ask, he said, just how much Grange the company made. There were five or six writers in this little group and suddenly, every single one of us had pad and pen poised. The production of Grange is a national secret that is not to be disclosed under pain of death (general consensus puts it at, depending on the vintage, between 5,000 and 15,000 cases, with most releases in the mid range, but this is pure speculation).

Gago was at a loss. The boss of bosses had just asked him a direct question and Gago is far too polite not to answer but knew he couldn’t give that information out in public. He managed a fair bit of mumbling and generalizations and I think he suggested they meet later. Pads and pens all went back into bags, and we could not help grinning while Gago looked like he’d just swallowed a bad oyster.

Gago was born in England in 1957, but his family moved to Melbourne when he was only six years of age. Originally a math teacher (teaching is still a passion), he undertook a science degree at the University of Melbourne and then attended Roseworthy College, a famous Australian winemaking college, graduating as Dux (the highest ranking academic performance -ed), which will surprise no one.

In 1989 he joined Penfolds as a sparkling winemaker, working with Ed Carr, who has established a career in sparkling wine (now with Arras) as successful as Gago’s is with table wines. He moved to reds and quickly rose through the ranks until succeeding Duval in 2002. In the 73 years since Schubert was first appointed, Gago is only the fourth chief winemaker.

During his tenure, he has stacked up an extraordinary array of bling, as has Penfolds under his stewardship (Gago heads a team of eight winemakers for table wines and a couple more for fortifieds). He has several “Winemaker of the Year” awards from different entities and publications, both from Australia and abroad, but the accolades go well beyond that.

In 2017, in what is termed “the Queen’s Birthday Honors List,” he was awarded the highly prestigious Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) for service to the wine industry. For non-Aussies, that is a big one! A year later, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of South Australia and named the Great Wine Capitals Ambassador for South Australia.

Very recently, Gago was awarded perhaps the most prestigious honor of all in the wine world: admission to the Decanter Hall of Fame (previously they honored the Decanter Man – or Woman – of the Year, but that changed). Decanter is a highly respected English wine magazine that established its hall of fame in 1984 with Serge Hochar from Château Musar in Lebanon the first recipient. There is only a single addition per year. Gago is the fourth Australian following Max Schubert in 1988, Len Evans in 1997, and Brian Croser in 2004. That two of the four chief winemakers from a single producer have made this list (Schubert and Gago) is unprecedented but shows just where Penfolds sits in the pantheon of wine producers around the globe.

And should you still remain unconvinced then take a moment to look at some of the names Gago has joined: Parker, Spurrier, Tchelistcheff, Robinson, Moueix, de Villaine, Antinori, Lichine, Gaja, Symington, Loosen, Guigal, Torres, Draper, Peynaud, Mondavi, and so many more. There is no question that the name Peter Gago sits very comfortably alongside them all.

What is most important is that across the board the Penfolds wines have never been better, and while it is a team effort, in the end we can thank Gago.

Winery

After the success of early sherries and fortified wines, founders Dr Christopher and Mary Penfold planted the vine cuttings they had carried on their voyage over to Australia. In 1844 the fledging vineyard was officially established as the Penfolds wine company at Magill Estate.

As the company grew, so too did Dr Penfold's medical reputation, leaving much of the running of the winery to Mary Penfold. Early forays into Clarets and Rieslings proved increasingly popular, and on Christopher's death in 1870, Mary assumed total responsibility for the winery. Mary's reign at the helm of Penfolds saw years of determination and endeavour.

By the time Mary Penfold retired in 1884 (ceding management to her daughter, Georgina) Penfolds was producing 1/3 of all South Australia's wine. She'd set an agenda that continues today, experimenting with new methods in wine production. By Mary's death in 1896, the Penfolds legacy was well on its way to fruition. By 1907, Penfolds had become South Australia's largest winery.

In 1948, history was made again as Max Schubert became the company's first Chief Winemaker. A loyal company man and true innovator, Schubert would propel Penfolds onto the global stage with his experimentation of long-lasting wines - the creation of Penfolds Grange in the 1950s.

In 1959 (while Schubert was perfecting his Grange experiment in secret), the tradition of ‘bin wines' began. The first, a Shiraz wine with the grapes of the company's own Barossa Valley vineyards was simply named after the storage area of the cellars where it is aged. And so Kalimna Bin 28 becomes the first official Penfolds Bin number wine.

In 1960, the Penfolds board instructed Max Schubert to officially re-start production on Grange. His determination and the quality of the aged wine had won them over.

Soon, the medals began flowing and Grange quickly became one of the most revered wines around the world. In 1988 Schubert was named Decanter Magazine's Man of the Year, and on the 50th anniversary of its birth, Penfolds Grange was given a heritage listing in South Australia.

Despite great success, Penfolds never rests on its laurels. In 2012 Penfolds released its most innovative project to date - 12 handcrafted ampoules of the rare 2004 Kalimna Block Cabernet Sauvignon.

Two years later, Penfolds celebrated the 170th anniversary – having just picked up a perfect score of 100 for the 2008 Grange in two of the world's most influential wine magazines. Today, Penfolds continues to hold dear the philosophies and legends – ‘1844 to evermore!'.