Viberti Giovanni Langhe Nebbiolo DOC 2021

Style: Red Wine

Closure: DIAM Cork

Viberti Giovanni Langhe Nebbiolo DOC 2021

Warehouse

34 Redland Drive

Vermont VIC 3133

Australia

Critic Score: 93

Alcohol: 14.0%

Size: 750 ml

Drink by: 2032

Viberti Giovanni was founded in the early 1900s when Antonio Viberti purchased the Locanda del Buon Padre with an adjoining vineyard in the village of Vergne, located in the commune of Barolo. Today, grandson Claudio manages the family business, which sources grapes from eight estate cru vineyards in Barolo and two contract cru vineyards in Verduno and Monforte d'Alba.

The Viberti Giovanni Langhe Nebbiolo DOC is made from 100% Nebbiolo sourced from their vineyards across the communes of Barolo, Monforte d'Alba and Verduno.

"Cherry jam, raspberry, floral top note, liquorice root. It’s juicy and red fruited, new leather, cranberry acidity and sweetness, firm and chalky, grainy finish and rosehip tea finish of good length. Very good." Gary Walsh

"Medium intensity ruby red. Aromas of ripe red fruits, strawberries and cherries. Soft tannin and great drinkability. After the destemming-crushing, maceration and alcoholic fermentation takes place on the skin for 8-10 days in temperature-controlled steel tanks. Malolactic fermentation follows at controlled temperature in steel tanks. Aging takes place for a year in wooden vats with a capacity of 50 hl each. The wine then returns to steel tanks where it completes its maturation for a further year." Viberti

Expert reviews

"Cherry jam, raspberry, floral top note, liquorice root. It’s juicy and red fruited, new leather, cranberry acidity and sweetness, firm and chalky, grainy finish and rosehip tea finish of good length. Very good. Drink: 2023-2030+." Gary Walsh, The Wine Front - 93 points

Piedmont Nebbiolo

The Piedmont wine region is located in the north-west corner of Italy. The name Piemonte means "at the foot of the mountains", the mountains in this case being the Alps. Piedmont is just Italy’s seventh largest wine region, but what it lacks in quantity it makes up for in quality.

Piedmont is famous for its Nebbiolo wines. Nebbiolo, the most exalted wine variety of Piedmont, gets its name from the Italian word for 'fog', nebbia. During harvest, which generally takes place late in October, a deep, intense fog sets into the Langhe region where the Nebbiolo vineyards are located. The Nebbiolo heartland is the tiny Barolo production zone, a cluster of fog-prone hills around the village of the same name.

Nebbiolo is early-budding, but also late-ripening. It needs good weather and lots of sunlight to achieve full ripeness, which is why the best vineyards for growing Nebbiolo are located on hillsides that are exposed to plenty of sunlight. Hence the suitability of the slopes of the Langhe hills near the town of Alba. Nebbiolo is only planted on the hills at an altitude above 250m, as fog hangs over lower vineyards for large parts of the day and there is no chance of making decent wine from this late-ripening variety if it is not exposed to maximum sunshine. The lower vineyards are generally planted with Barbera or Dolcetto.

Soil types also play a crucial role. Nebbiolo thrives on calcareous marl, a lime-rich mudstone that is found on the right bank of the Tanaro River, home to the famous appellations Barolo and Barbaresco. Nebbiolo grapes grown on other soil types tend to make wines that are not as aromatic and elegant.

Nebbiolo produces a full-bodied wine with high levels of acidity and tannin, particularly when it is young - at odds with its light colour. It also has great aging potential – particularly the Barbaresco and Barolo wines that garner the highest price tags.

The two highest classifications of wines produced from Nebbiolo in Piedmont are the DOCG denomination Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (Denomination of Controlled and Guaranteed Origin) and the DOC denomination Denominazione d'Origine Controllata (Denomination of Controlled Origin).

In total, there are seventeen DOCG and DOC wines made in Piedmont. The five applicable to Nebbiolo are Barolo DOCG, Barbaresco DOCG and Nebbiolo d’Alba DOC (which must be made from 100% Nebbiolo) and Roero DOCG and Langhe Nebbiolo DOC (which must be made from at least 85% Nebbiolo).

DOCG and DOC Nebbiolo production zones in Piedmont

Barolo DOCG is perhaps the most famous Nebbiolo wine. Its name derives from the small town in the heart of the Barolo production zone, but it is produced in eleven communes around the larger hillside towns in the area. Barolo DOCG wines must be made from 100% Nebbiolo and must age in oak for at least 18 months with a total age time of 38 months before release. Barolo Riserva DOCG must age in oak for at least 18 months with a total age time of 62 months before being released.

Barbaresco DOCG is often described as more elegant than the more powerful Barolo, the 'queen' to Barolo’s 'king'. Barbaresco DOCG wines must be made from 100% Nebbiolo. The production zone is tiny, a third of the size of Barolo, and has less stringent regulations. Barbaresco DOCG wines must age in oak for at least 9 months with a total age time of 26 months before release. Barbaresco Riserva DOCG must age in oak for at least 9 months with a total age time of 50 months before being released.

Nebbiolo d’Alba DOC is produced between Barolo and Barbaresco. Near the two zones the wines are full-bodied and age very well. Further away, they’re delicate and best drunk young. This wine can also come from grapes from Barola or Barbaresco not quite up to heavenly standards, such as grapes from new vineyards in the famous hills or from less exalted vineyards. Nebbiolo d’Alba DOC wines must be made from 100% Nebbiolo and must age for at least 12 months before release. Nebbiolo d’Alba Superiore DOC wines must age in oak for at least 6 months with a total age time of 18 months before being released.

Roero DOCG is a little known zone just north of Barolo within the Langhe. Roero DOCG wines must be at least 95% Nebbiolo and must age in oak for at least 6 months with a total age time of 20 months before release. Roero Riserva DOCG must age in oak for at least 6 months with a total age time of 32 months before being released.

Langhe Nebbiolo DOC falls in (is a subset of) one of the largest wine zones in Piedmont, Langhe DOC. The Langhe DOC covers 54 communes of the Langhe and Roero hills. Varietally focused wines can include the name Langhe plus the grape. All told, there are 23 different forms of Langhe wines with Langhe Nebbiolo being just one. Langhe Nebbiolo DOC wines can come from anywhere in the Langhe i.e. from any of the four zones above (Barolo, Barbaresco, Nebbiolo d’Alba or Roero). Langhe Nebbiolo DOC must be at least 85% Nebbiolo and allow for up to 15% of other indigenous grape varieties, such as such as Barbera and Dolcetto. In practice most are made entirely from Nebbiolo.

Serralunga d'Alba in Piedmont, where the Nebbiolo grape is king

Langhe Nebbiolo

The following text is taken from an article by Kevin Day titled 'First-Taste Guide to Langhe Nebbiolo' at www.openingabottle.com

There are many ways to define "fine wine". Perhaps it is a wine that can age, or a wine that will increase in value. Maybe it is just a wine that is perfectly balanced and timeless. However, in terms of drinking culture, it is fairly straightforward: a fine wine is a wine people fuss over. They catalogue it, chart its vintages, obsess over when to open it, how to open it, whether to decant it, and at what exact temperature to serve it. If all this fuss has turned you off to fine wine - yet drinking well is still important to you - then allow Langhe Nebbiolo to step up to the plate.

Hailing from the iconic Barolo and Barbaresco zones of Piedmont, Italy (as well as numerous adjacent hillsides), this broad category of red wine showcases the earthy flavors of Nebbiolo with just a hint of the zone’s characteristic gravitas. It can hold its own at an important feast, yet be affordable enough for you to pick up a second or third bottle so no one goes thirsty. And its tannin profile is rarely severe enough to call for cellar-aging or decanting. Just pop, pour and indulge.

"Langhe Nebbiolo could be very, very light and very fresh," says fifth-generation winemaker Alfio Cavallotto of the eponymous Barolo estate. "Or, as in our case, the wine is a fantastic wine for aging. So there are many, many different styles."

But, he cautions, "it’s complicated." Complicated in a good way. Langhe Nebbiolo’s spectrum of styles stems from the diversity of the winemaking families that have come to define the region. Some are fiercely traditional. Some are experimental.

In the Langhe Hills, the grape reaches its most intense expression in the form of Barolo. The Langhe Nebbiolo category was designed to give producers a quicker-to-market Nebbiolo wine to sell while the bigger, bolder wines mature in the cellar. By its nature, it is more affordable for consumers.

Let’s be honest: for all of its glory, Barolo and many top Barbaresco can be a bit of a bear in youth. Langhe Nebbiolo wines tend to be more focused on freshness and fruit, without entirely sacrificing the savory and earthy character that the grape (and the region) is known for. You won’t be laying these wines down in your cellar (though you certainly could with some), but you are likely to be drinking them more often given their cost. And as far as dinner guests go, they’re delightful company.

The first thing to know about these wines is what the word Langhe refers to - a series of captivating hills rising south of the city of Alba. Its name is a derivation of "tongues", likely because of their ridge-like shape.

It is in the Langhe that we find the small villages of Barolo and Barbaresco, and the protected appellation-based wines in their name. Made from the beguiling Nebbiolo grape, these highly refined wines can age for decades. Their singularity and complexity have resulted in international acclaim, as well as high prices. Protecting the brand behind these village names are some of the most stringent regulations in Italy. For example, Barolo requires 38 months of aging with 18 of those months spent in an oak vessel.

These are not wines that you typically open at release. In order to tease out their details and optimize your sensory experience, anywhere from five to 10 to 20 years of cellaring the wine is ideal. Which begs the question: what should we drink in the meantime?

The role of Langhe Nebbiolo in Barolo and Barbaresco

Alfio Cavallotto explained to me that before the creation of the Langhe DOC, producers within the Barolo and Barbaresco zones were more limited in their production options, particularly with their younger vines of Nebbiolo. Young vines can be more vigorous and fruity, but - as Cavallotto noted - they often do not yield the proper structure for Barolo. Replanting vines is a necessity at times, but growers in the area were faced with two unsatisfying options: wait 10 to 15 years to use the fruit from their plantings or have a less-structured final wine.

It quickly became apparent that a so-called "second wine" category was needed. Popularized in Bordeaux but adapted for use in places like Montalcino, a second wine is essentially a simpler, more quenching version of a prestige wine. Often, they rely on the fruit from younger vines or slightly less-than-ideal vineyard exposures. As the wine industry grew increasingly international in the 1990s, Barolo and Barbaresco winemakers saw a need for such a wine. However, they had another hurdle to clear: few people even knew about Nebbiolo’s varietal character. They may have known about Barolo, and in some cases Barbaresco, but not the grape that made them.

"I remember in the 1980s and ’90s it was very, very difficult to sell Nebbiolo outside of Italy in the foreign markets," Alfio recollected, speaking of the varietally labeled wines. "But after a while, some customers began to taste some [Langhe Nebbiolo] and they said 'oh wow.' It’s not Barolo, but it is a food wine. It is very approachable, very drinkable."

The Appellation Rules

Piedmont is fiercely committed to the idea of appellations of origin. Producers simply don’t freestyle here like they sometimes do in Tuscany, Sicily or Veneto. As a result, Piedmont does not have an IGT wine category.

That said, the winemakers are not stuck-in-the-past either. As Barolo and Barbaresco began to achieve international fame in the 1980s and 1990s, several other needs emerged for local producers — beyond just what to do with younger vines in Barolo and Barbaresco. Awash in red wines from local, little-known grapes, the temptation to diversify with international varieties — particularly whites like Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Riesling — prompted calls for new denominations.

"For us producers, we should be free to make what is the best thing," Alfio stated.

It was with this in mind that the Langhe DOC was created in 1994 to give winemakers more latitude with their winemaking, while preserving the tradition of not only the Barolo DOCG and Barbaresco DOCG, but also Barbera d’Alba DOC and Dolcetto d’Alba DOC.

The Langhe DOC covers 54 communes of the Langhe and Roero hills. Rosso and Bianco designations refer to blends, while varietally focused wines (a minimum of 85% from a single grape) can include the name Langhe plus the grape. All told, there are 23 different forms of Langhe wines with Langhe Nebbiolo being just one.

Here’s where it gets complicated for consumers. There already existed a category for non-Barolo/non-Barbaresco Nebbiolo wines: the Nebbiolo d’Alba DOC. Created in 1970, it was intended for producers with quality Nebbiolo vineyards outside the two prestigious zones. With the creation of Langhe Nebbiolo, these producers suddenly had two paths to pursue: follow the more stringent aging requirements for quality of the Nebbiolo d’Alba DOC, or go with the increasingly more recognized (but more open-ended) regulations of Langhe Nebbiolo DOC.

"In the last 10 years, I think that Langhe Nebbiolo - in my opinion - has become much more important than Nebbiolo d’Alba," notes Alfio Cavallotto, adding that the evolution in quality for the former has largely negated the intent of the latter’s more stringent rules. "I suspect that in the future we will have just one denomination - Langhe - for everybody."

The spectrum of taste in Langhe Nebbiolo

One way in which the quality revolution of Langhe Nebbiolo has eclipsed that of Nebbiolo d’Alba lies in terroir. Since Langhe Nebbiolo fruit can come from Barolo and/or Barbaresco vineyards, the wines can essentially be "“declassified" versions. But what exactly does that mean?

Barolo draws its magic from 170 designated vineyards, while Barbaresco is smaller, and contains 66 named geographical units. These vineyards are mostly planted to Nebbiolo, but there are some exceptions. Since this grape is particularly terroir-sensitive, winemakers have a lot of options to choose from depending on each plot’s sun exposure, drainage and most importantly — for purposes of Langhe Nebbiolo — vine age. As we noted above, the younger vines (typically under 10 years of age) have an exuberance to their fruit that matches better for Langhe Nebbiolo. Meanwhile, the older vines tend to give lower yields but high concentration, more structure and complexity. (Note: Winegrowers are not obliged to use only young-vine fruit in Langhe Nebbiolo. They have the latitude to select older vines if they choose, but typically they are reserved for the highest-level wines).

This would be the first scenario in which Langhe Nebbiolo could function as a declassified Barolo (or Barbaresco, for that matter). The producer simply harvests and vinifies the younger vines separately.

The second aspect is what occurs in the winery, and here is where we find the spectrum of Langhe Nebbiolo stretching. Some producers will allow the grapes to macerate for a short time, then allow the wine to settle in a neutral vessel, such as a stainless-steel tank. The aim? Fruity tones, freshness and a softer texture. In other words, easy consumption.

Meanwhile, other winemakers - such as Cavallotto as well as Vietti and Produttori del Barbaresco, to name just a few - will employ the same extended-fermentation technique (anywhere from 14 to 30 days) that they would use for their Barolo or Barbaresco. The goal here is to extract Nebbiolo’s structure and aromatic complexity as much as possible. Usually, a producer who has chosen this path will also aim to age the wine in an oak vessel of some kind to allow the wine’s piercing acidity and pronounced tannins some time to evolve. New oak and American oak are generally avoided for this reason: they impart too much oaky personality to an already structured wine.

When I asked Alfio why they chose to make such a structured version of Langhe Nebbiolo, his response was matter of fact.

"We are a very historical, old family and we are exactly in the center of Barolo. Speaking about Nebbiolo for us …" He paused and shrugged a bit, "Nebbiolo is a Barolo." In other words, what other style could they possibly make that said anything genuine about them? But he also noted that their lack of vineyard holdings outside Barolo - and even their lack of less-than-prime vineyards inside Barolo - led them to this identity.

"Probably my father and uncle - also my grandfather - they weren’t so great businessmen. We have always been farmers and have never wanted to grow the business much."

And in many ways, that statement defines the spectrum of Langhe Nebbiolo most precisely. Some are borne out of business ambition and a desire to round out a portfolio of wines. Others are merely a place to bottle the younger grapes from the area’s signature terroir.

In fact, I believe that no other wine in the area transmits the identity of these families more quickly and easily than their Langhe Nebbiolo. For all their majesty, Barolo and Barbaresco take ample time and study to fully appreciate. That’s what makes them so compelling, so irresistible and yes, even so maddening. In short, that’s what makes them a fine wine.

But in the space between those bottles, I’m glad we have Langhe Nebbiolo to play with. It’s a way of getting to know the winemaking families of the Langhe.

The winery

Viberti Giovanni was founded in the early 1900s when Antonio Viberti, an innkeeper and restauranteur, purchased the Locanda del Buon Padre with an adjoining vineyard in the village of Vergne, located in the commune of Barolo. In 1923, he began producing wines exclusively for the patrons of the family restaurant, Trattoria al Buon Padre, from Dolcetto, Barbera and Nebbiolo grown in the estate vineyard. In 1955, Cavalier started selling his Dolcetto d'Alba, Barbera d'Alba and Barolo at local markets.

In 1967, Antonio's son, Giovanni, joined the family business to manage the inn and adjoining cellar. A new winery was constructed and the vineyard expanded. Supported by his wife Maria, head chef of the family and restaurant kitchen, the winery and restaurant went from strength to strength. Their wines were promoted by the inn's constant visitors from neighbouring Switzerland, Germany and Austria, and in 1974, the first Viberti wines were exported to southern Europe to satisfy the growing demand outside Piedmont.

Giovanni's eldest son, Gianluca, joined the family business in 1989 after graduating from the Enological School of Alba. The winery started bottling single vineyard Barolos, introduced new winemaking techniques and began exporting to the emerging US market.

In 2004, Claudio, Giovanni’s third son, joined his brother at the winery. He oversaw the start of a substantial investment in Barbera, replanting the vines with much tighter spacing and dropping yields to produce higher quality Barbera. A new flagship wine was born, Barbera d’Alba La Gemella, named in honour of Maria who was a twin and a major driving force behind the family's success. Maria had insisted over the years that the family keep making Barbaera d'Alba and often lamented how many of the beautiful local Barbera vineyards had been replanted with the more profitable variety Nebbiolo.

Claudio took over management of the family winery in 2008 while Gianluca, after more than twenty years tending the family vineyards, left to establish the new Casino Bric 460 winery nearby. Claudio acquired new vineyards in Barolo and negotiated contracts with growers in Monforte d'Alba and Verduno to supply grapes for the historic Barolo Buon Padre label. Investment in new vineyards for the growth of Barbera Gemella continued.

Today, Viberti produces 120,000 bottles a year and exports to over 25 countries worldwide.

The Vineyards

The estate vineyards are the beating heart of production and are managed with extreme care and attention to detail. They are mainly located on the west side of the City of Barolo, at an altitude of 400 - 500 meters above sea level. Nebbiolo, Barbera and Dolcetto, together with a tiny amount of Chardonnay are grown.

Viberti own eight vineyards in the commune of Barolo, in the crus of Bricco Delle Viole, San Pietro, La Volta, Fossati, Terlo, Albarella, Ravera and San Ponzio. In addition, they source grapes from vineyards in the Monvigliero cru of Verduno and Perno cru of Monforte d'Alba (refer to the map below).

Reserve Barolos are produced from the crus of Bricco Delle Viole, San Pietro, La Volta and Monvigliero.

The historical Barolo cuvée Buon Padre (first produced in 1927) is today a skillful assemblage of the 10 crus across the communes of Barolo, Monforte d'Alba and Verduno.

The vineyards of Viberti in Barolo: O are estate-owned vineyards, P are contract vineyards (grapes are purchased)

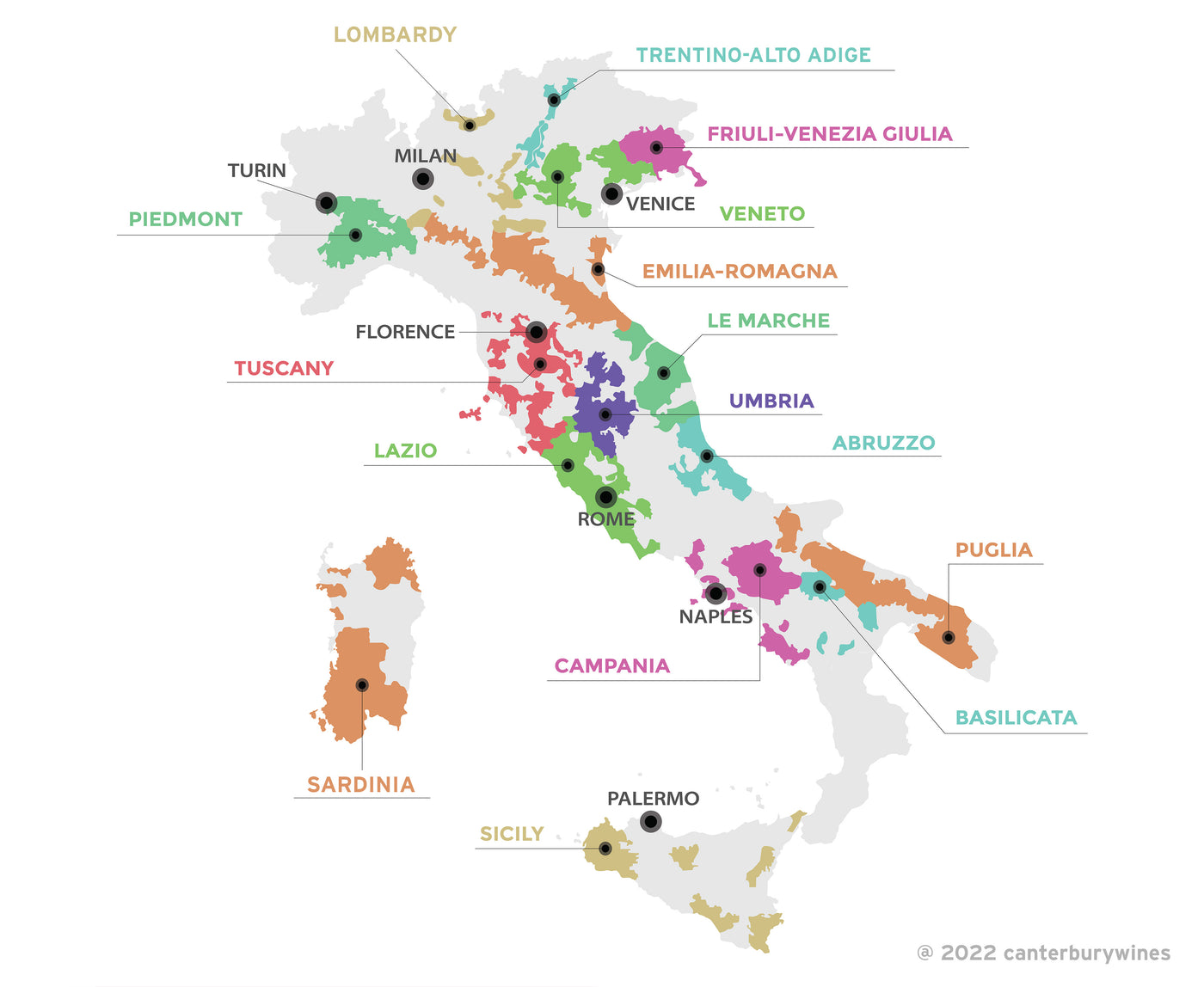

Italy

There are 16 major Italian wine regions, each known for their own unique grape varieties, terroir and wines. They are Abruzzo, Basilicata, Campania, Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Lazio, Le Marche, Lombardy, Piedmont, Puglia, Sardinia, Sicily, Trentin-Alto Adige, Tuscany, Umbria and Veneto.

Italy was the leading producer of wine in the world in 2020, with more than half the production coming from the four regions of Veneto, Apulia, Emilia-Romagna and Sicily. More than 400 grape varieties are grown across the country’s wine regions, most of which are indigenous.

Italy's most esteemed wine regions are Piedmont, home to Barolo and Barbaresco, Tuscany, home to Chianti, Brunello di Montalcino and Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, and Veneto, home to Soave, Prosecco and Amarone.

Italian wine is labelled by wine region or appellation rather than by grape variety. In order to guarantee the quality and provenance of Italian wines, the government established an appellation quality system. Wines with a regional designation are classified as IGT, DOC or DOCG. There are currently 330 DOC appellations in Italy, but it is a number that is expected to grow rapidly in the coming years. The region with the biggest number of DOCs is Piedmont with 42. To date, there are 77 DOCG appellations in Italy and the region with the biggest number of DOCGs is Piedmont with 16.